BEA’S BENCH, TREMPELEAU REFUGE

(Copyright 2020 by Richie Swanson)

This commentary appeared in The Wisconsin State Journal, La Crosse Tribune, Winona Daily News and Red-headed Woodpecker Recovery Project Newsletter during spring 2020

I first met Bea Stellpflug in 1980 at Trempealeau National Wildlife Refuge, and she laughed at how her daughters told her to stay away from the dangerous-looking guy who lurked around the bushes and bulrushes. Forty years later, I practice citizen-science from the bench placed at the refuge in memory of Bea, watching one of her favorite birds, the redheaded woodpecker. The sun rises behind me, and the light of friendship bolsters me during the Covid-19 pandemic.

I was indeed suspicious-looking: a long-haired, tangle-bearded long-distance bicyclist who worked very part-time and spent whole days just listening to birds. Bea drove a pickup, wore glasses with rims nearly as big as her smile. She loved country music and casinos, and her husband owned an independent tire and equipment business on their home farm in the town of Trempealeau. Bea had six kids. I minimized my footprint, fathering none. I was totally counter-culture, mistrusting capitalism.

But Bea asked if I’d seen the “redheads” feeding on acorns after cars crushed them on the refuge’s roads, and we became thick as thieves. We each volunteered on annual sandhill crane counts, watching through cold April dawns as cranes bugled alarm calls from increasing sites each spring, rebounding from a near extinction during the 1930s.

Bea died of a stroke in 2012, 74-years-young. Last May I happened upon warblers flashing their marvelous colors all around her bench, and I heard Bea’s voice jump, seeing her eyes brighten again. “Blue-wing! Redstart! Blackburnian!” Sandhill cranes bugled explosively from a marsh, and I remembered the pair who had called the day I had chanced to meet Bea after she had finally returned to the refuge after a hip replacement. We crept across hummocks to view the cranes, and she stepped on a snake nest, fell hard on her hip, and there I was, only a bicycle for transport, years before cell phones. But Bea had bounced up, instantly recovering the fluster of happiness that expressed her love of nature.

Now a redhead called from an island opposite her bench. It wagged its head at two other redheads, chortling, “Quirr! Kikarik!” Later one clung to a hole, fanning its wings, tipping in. It poked out its scarlet head and called. It swiveled and bobbed on a branch with a second redhead, and I filled out a form for the Redheaded Woodpecker Recovery Project. Courtship behavior at a nest site. Bea would have bubbled over with joy.

When I bicycled in farm country decades ago, redheads flushed ubiquitously from roadside ditches. They created all-day commotions, “rattle-calling” from corn cribs and playing “hide-and-seek” around campground-trees. They cavorted in dead elms in pastures and cached acorns in river birches in marshes. Now they’re hard to find. They’ve declined 67% since 1970—nearly 95% in Minnesota, says the Redheaded Woodpecker Recovery Project.

The Audubon Chapter of Minneapolis formed the recovery project in 2006, determined to identify the causes and cures for the decline. They rely upon science just as coronavirus efforts do today. Volunteers go out at dawn to survey nest sites, and at dusk to find roost sites. They record distances between nests, how parents feed young, how young forage for themselves. They count acorns in oaks, trying to understand the role they play in redheads’ lives.

Redheadrecovery.org describes the recovery project. It’s centered at Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve in Anoka County, Minnesota. It’s steadfastly uncovering the species’ needs, and urges landowners to leave big dead trees standing and to regularly burn savannas. It’s discovered polyandrous red-heads, females reproducing with two males the same season. It uses isotope analysis to learn diets, cameras to determine nest results, and tracking devices to study why redheads migrate some winters and remain north others.

As “Bea’s redheads” incubated eggs last June, two Trumpeter swans and five cygnets appeared in a nearby marsh. Proof that science works. Wisconsin reintroduced the species in 1989, and this marked the refuge’s first successful brood. Bea would’ve have been “on eggs,” driving from the trumpeters to the redhead nest, worrying over their fates. Mid-June, her redheads brought insects into the hole for chicks. Feedings continued through early July–long enough to suggest young fledged successfully. Bea would’ve smiled, “Next year I’ll count them as they come out the hole.”

I sat on her bench last week, and a lone redhead called from last year’s nest-tree. It lit after a second redhead, returned to the tree, tapped. It bent halfway into a new hole, excavating this year’s cavity. I recorded the behavior, though coronavirus has cancelled the recovery project’s volunteer activities in 2020. I practiced social-distancing and seemed to watch the redhead alone. But anyone who’s teamed with others to sustain the miracle of life knows I was blessed by good company.

Information in text updated August 15 2021

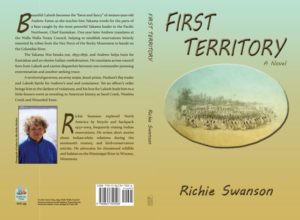

The nest cavity opposite Bea’s Bench, photo by Lisa Reid.