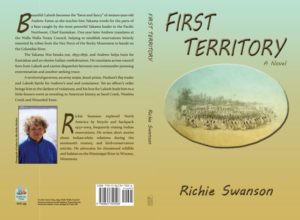

FIRST TERRITORY: A NOVEL

Sunstone Press 2013

In First Territory, nothing can dampen the love of a 16-year-old white settler for a young Yakama woman. Andrew Eaton translates for both Lalooh’s Indian band and Washington Territory during the Walla Walla Treaty Council and the U.S. invasion of Yakama homelands, 1855-1856. Andrew finds himself embroiled in duplicitous treaty maneuvers, an extermination policy and the rape of an innocent Yakama woman by territorial troops. Scroll down to read a free excerpt.

PRAISE FOR FIRST TERRITORY

First Territory “is truly a marvelous read…Andrew maneuvered through the story as a real human might. Not once did his view, thoughts or feelings read with anything other than reality…And Lalooh, I absolutely loved her, her point of view and her actions.”—Louis Kraft, author, Custer and the Cheyenne: George Armstrong Custer’s Winter Campaign on the Southern Plains; Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway, Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road from Sand Creek, etc.

“The writing is breathless,” said Sue Ellis, reviewer, Prick of the Spindle Magazine. “First Territory is altogether the most convincing piece of historical fiction I have ever read.”

Swanson “drives home what a gutsy, well-schooled novelist can do when endeavoring to rise above the average storyteller,” said Phyllis Morreale-de la Garza, Old West Book Reviews.

First Territory is distributed by Ingram and available at bookstores and online dealers–Bookshop, AbeBooks, Amazon etc.

RADIO INTERVIEW

https://beta.prx.org/stories/224961.

Richie discusses how visiting Indian reservations on bicycle trips led him to write First Territory and other fiction about the U.S. invasion of Native homelands.

FREE EXCERPT

FIRST TERRITORY

The first 12 pages

(Copyright 2013 by Richie Swanson)

ONE

The Indian who claimed to own the Umatilla ferry was nowhere along the bank, and I wondered out loud if the governor was the kind to bristle at a delay, but Dominique merely nodded at two canoes poking from beneath willows. He smiled a petite grin for a big-shouldered man, his face leathery, brown as if stained by walnut juice, his lips and high-flung pompadour French-looking, his gaze swamp-water dark, savage from wintering and marrying in frozen caribou wilderness, but shrewd too, grim and confident from his British blood and schooling, and cajoling from factoring at Hudson’s Bay posts from the Saint Lawrence to Jasper country and finally to Fort Walla Walla. He reached beneath our wagon and pulled a whipsaw from between two long boards, and we sweated like demons, cutting planks from driftwood, and we piled them into the canoes, so the wagon-wheels would not cut through, and I laid a wobbly board in, and he flung it toward the Umatilla’s mouth. “No, you cannot lie out here, not to yourself, not to anyone, not about anything, never!” He glanced at the Columbia boiling and thundering three-miles wide, glaring blindingly in the mid-morning heat. “Your lie might take us across the little-piddling Umatilla, but you tell yourself weak is strong, wobbly is solid, your habit will kill someone someday.” Dominique scoffed. “The governor might growl, but he’s making treaties like a grizzly nipping a sow too early. The army—General Wool—would leave the interior to the Indians for now.”

We unloaded the treaty-gifts, lifted the wagon’s wheels into the canoes, reloaded, and I rode my bay roan into the Umatilla, and Dominique braced a log against the wagon, pried the front in, jumped on. He leaped the load jackrabbit-like. He took the reins, and I led the oxen swimming and gawking in terror, the wagon knocking and slamming, the canoes splashing and slapping. The wagon stayed high. The oxen came out un-stumbling, and we left the canoes full of planks splintered by the steel wheels. “See?” said Dominique. “A lie is like an Indian. You must be firm sometimes, must hold a pistol to its head, so it does not rob you.”

“Plain enough.”

“Ever translated at a council before?”

“No.”

“You seem too young.”

“Well, I told you I was only five when my folks emigrated.”

“Who taught you?”

I shrugged to put him off. I yelled to the team, and he whipped them. We rode along the right bank of the Umatilla, and he left his question alone, but then a long-steep pull brought us atop a sun-burnt plain, and he caught me gazing through the white-earth shimmer toward Yakama country, thinking of Lalooh, her pretty-arched cheeks moistened by clouds of cold-air vapor, her sweet-water voice chattering mysteriously over hard-tongued words the night my brother and I had met her. Jake and I had led mounts and pack horses down a quiet-powdery trail and had reached the frozen Yakama River before we had expected, and Lalooh had stood alone in snowshoes on the ice, lurching, her eyes twinkling candle-like, her braids oiled beneath the starlight, the rest of her covered darkly by a buffalo robe. She eyed the snow on the blankets behind our saddles, the frost in Jake’s beard, the raw-red flesh of my younger-peachier face. She peered quickly upriver, guessing we had been aiming for the fire-lit lodge ahead, and then she signed with her hands, showing how the snow had caved in the roof of Father’s Sidalia’s cabin. Were we the black gown’s new carpenter and farmer?

Jake and I nodded, dismounting, and four braves walked from the bend behind Lalooh, carrying an old gray-haired Indian, bolstering his limbs as he sang in Yakama, his eyes roiling in trance. “Almcotty,” said Lalooh, speaking his name, adding a single word in Chinook, the old trade language. “Plet.” Priest. The braves carried Almcotty past us, and Lalooh and the Yakama went briskly upriver, trusting their backs to us, Lalooh glancing over her shoulder, a wisp of a smile sparkling, and Jake and I followed, and braves descended banks, filing numerously behind us–then squaws, then children crying hunger pangs, stepping around steers and milk cows sprawled on the bank, their bones near-poking out their hides–stock starved to death. We passed cows standing where they had died stupefied with hooves frozen in snow, and then we climbed toward the lodge of tule mats, and the Yakama started to chant, and the braves lowered Almcotty. An old squaw took our guns and horses, and we were whisked inside, left alone, pressed against a wall. One hundred Yakama whooped, then two hundred. Almcotty yelled above them all. He ordered the braves in line, the squaws, the children. He waved, and drummers pounded pom-poms, and Almcotty shrieked, leaping high, springing sideways like a deer, and every savage danced, everyone in line, jerking arms and legs, sweating, dropping to the floor, Lalooh in front, Lalooh shuffling all night, Lalooh’s braids bouncing lightly, Lalooh lifting her chin like a princess, her stare flaming copper, holding me against the wall, saving me from glancing in terror at Jake.

Finally a dawn breeze fluffed the lodge, and the Indians rushed out. The snow was gone, and horses were foraging, and Lalooh laughed a softly tinkling bell beside me, naming the wind so sudden and warm, “Chinook.” “Plet,” she said again, running the two ideas together, her breath washing my cheek warmly, damply, close.

And then Father Sidalia came sloshing up the bank, walking with a shepherd’s staff, bending and swaying like a thin-dark reed, his bare feet moving in a frozen crust turning swiftly into gumbo, his dimples rising blissfully as he chanted a primitive Indian rhythm and sang in deep tenor about Christ entering Jerusalem, palms cut and laid at the savior’s feet.

“Chemookdatpas,” Lalooh had said. “Black gown.” She spoke English.

Only a few words, she had signed, and she had raised her chin my way, and I had felt a new world as large as the valley below, the clouds lifting rapidly, her bronze face waiting eagerly, her copper eyes shining radiantly beside me.

* * *

“Did you get to kissing her?” asked Dominique.

“Traded words for a year.”

“You Catholic?”

“No, Ma’s reverend in Brownsville told us Sidalia had lost his laymen and needed hands, and Jake and I went to see if what people claimed was true—that Kamiakan’s country could hold stock all winter.”

Dominique drew in his lips as if to whistle, to show the import of knowing Kamiakan and his band. He knew by heart and years what most of us guessed by hearsay, you see. During the late twenties he had given Kamiakan traps, shot, powder, dog sleds, even a beaver’s hat with fox tails and cock feathers–all to induce his band to trade furs with Hudson’s Bay Company—and all to no consequence. During the thirties he had sold American emigrants flour and tobacco and had directed them south away from the company’s beaver country—also to no consequence. The British border had moved up to the forty-ninth parallel in `forty-six, the Land Donation Act had passed in `fifty, California had become a state, and gold-and-settlement fever had swept the fur brigades from the Columbia country as cleanly as locomotives would soon whistle buffalo from the plains.

Washington became its own territory in `fifty-three, and the company offered to sell Dominique cattle and horses to raise. Dominique had declined, had left his son at Fort Walla Walla and had moved with his Babine wife to Oregon City in Willamette Valley. And a week ago his express had arrived at Jake’s claim above The Dalles, where I had been hewing fence posts for the boundary: “Assistant needed to interpret at the largest Indian council ever held west of the Rocky Mountains. If he proves himself able to speak Yakama, the governor will pay five dollars in gold per day.”

* * *

And so Dominique and I drove the team steady across the plain, and we called out Indian words, testing mine against his, and when the heat eased toward dusk, Dominique galloped the horses to a soaking lather, riding through salt weed to a hidden sink of cottonwoods, and he tossed sand on my cooking fire and passed me pemmican from the Cree on the Saskatchewan, moist with berries and buffalo juice, and we encamped invisibly, keeping ourselves as silent as the stars above us.

“Allons!” Dominique shook me in the morning, waking me in French as if I were a voyageur or bourgeois. He walked to wagon ruts at the edge of camp, grasses freshly cut for forage–signs of the governor’s party—it had left Fort Dalles two days before I had arrived there, and we had been ordered to catch it.

We drove the team past noon, and we pulled up at the rim of a crest, and Old Glory flapped from a wagon in the Walla Walla Valley below, a handful of Dragoons glittering magnificently on mounts around it, white breast-belts shimmering against blue uniforms, gilt buttons and scabbards winking before the gleaming-winding river, an ocean of prairie behind them.

We rode down, and there in the wagon-bed squirmed the first governor of Washington Territory, thumping violently against buckboards, looking hardly five-feet tall, his head oversized like a dwarf’s, his legs child-sized, his pants bunched down around his ankles as if he had soiled his drawers. The governor writhed, pulling up a hernia truss, his narrow-brash eyebrows knitted in pain, his beard immaculately trimmed but wrenched from his exertion–I had read about him in newspapers–he had come from blue-blood Pilgrims in Massachusetts—had suffered an old hay-pitching injury, a rupture from boyhood—had graduated first-in-class from West Point–had taken Mexico City with General Scott–had written election pamphlets for President Pierce–so had earned his appointment and had come out here, surveying railroad routes through the highest-snowiest passes of the Rockies and Cascades.

He finished tying his truss, and his orderly lifted him, and he braced himself against sideboards, pushing against a gold-handled cane, looking as lean and muscled as a mink on the prowl. He flashed a regal smile at Dominique, a cordial beam of his enormous eyes at me, and then everyone waited. He swung his body wincing and looked with menace at bare-wooden rails, an old fence enclosed. He looked at Dominique again, and a kind of prayerful silence passed between them. We had arrived at the site of the old Whitman mission, and we could see between the rails the grave markers of the fourteen Americans massacred eight years ago. But all other signs of Reverend and Narcissa Whitmans’ industry—the lean-to where they had first sung Protestant hymns to Indians, the fields and garden, grist mill and stock pens, emigrant house, mansion house trimmed in New England green, the medicine closet where two Cayuse chiefs had axed the reverend, the school from which a Cayuse boy had shot Narcissa, the fruit trees where Cayuse had taken Christian women, the kitchen where Cayuse had butchered a man my age, sick with measles—all were gone without a trace.

“Dominique!” said the governor. “Young Eaton! You will make it clear to the Cayuse that if any one of them gets saucy during the council, he will be seized!”

Dominique nodded coolly.

“Yes sir,” I said.

The governor wriggled sharply, and his orderly lowered him, and he lay flat again all the way to the treaty grounds.

* * *

And after dark he summoned me, and I stood by his wagon as he sat in the bed, leaning against the sideboards, working a sextant, his legs spread wide, a candle flickering on a crate beside him. He slid the index arm, fixed screws and lenses, looked and looked at the stars and a crescent moon, and then he thrust himself sideways and peered through a telescope I had not seen in the dark. He lifted a watch from the crate, then a thermometer, and he jotted notes, his face in the candlelight giant-looking, his eyebrows so painfully squeezed I dared not breathe or swallow. He reached around himself and put each instrument away in its case, and then he slid adroitly across boards, stood before me, moved instantly past, and I was ushered into his tent, and he received me sitting upon a simple army blanket on a wooden bed frame–almanacs, books and portfolios stacked in lantern-light all around him. He looked down at tables and columns of figures, hours of trigonometry awaiting him–coordinates to be ciphered by Greenwich Time, angular distances, refractions, the courses of heavenly bodies.

He looked up as if we were old friends. “Tell me,” he said, “did Chief Kamiakan leave last fall to plan a federation to kill all the whites in the Oregon country?”

Lalooh came to mind again, her taps last fall at the cabin door, her hurry as she had led us deep into willows up Ahtanum Creek–Sidalia had fled with us, carrying his satchel of accoutrements. “Kamiakan has returned,” Sidalia had said. “The clouds are gathering upon all hands. The tempest is pent-up and ready to burst.”

I looked at the governor directly. “I never heard,” I said.

“Can you remember last September?” said the governor. “If Kamiakan met with Looking Glass and any Cayuse chiefs? With Kahlotus? Peopeomoxmox? If he met with any Rogue or Spokane or coastal chiefs?”

I remembered how softly Lalooh had returned through the willows the next morning, how the yellow leaves had rustled so quietly Jake and I had drawn pistols before her smile had told us Kamiakan had allowed us to stay, at least through the coming winter.

I shook my head no to the governor, and he downed a cup of bourbon, exasperated. “Come on, my boy! My territory embraces eleven degrees of longitude! Six in latitude! God knows how many tongues! How many tribes! Is my question so hard?”

“I remember Kamiakan reciting letters to Father Sidalia, asking you to keep the whites out of his country. I remember Kamiakan roping his own longhorns and digging his own cabbages and turnips from his garden.”

“Did the superior of the mission—Sidalia–have a squaw?”

“No sir.”

“Did he and the other Catholic priests talk against America?”

“No sir.”

“Did they sell Kamiakan extra powder and balls?”

“No sir.”

The governor glared me out, tucking in his leg tiredly, stiffly, wearily.

* * *

But when the council opened three days later, he leaned from his cane as lithely as a lynx about to lunge, speaking forcibly, and Kamiakan seethed silently, motionlessly, a shadowy hulk seated beneath the council arbor, his face enormous, his nose broad and fleshy, his shoulders thrust backward as if to communicate his displeasure to semicircle after semicircle of surly-faced braves and squaws broiling in the sun on the ground behind him.

Dominique repeated each sentence of the governor’s in the dialect of the Nez Perce, the tribe more numerous than all the others combined. One crier shouted his translation in Nez Perce, another in Wallawalla. The governor’s Indian agent for the interior—Thomas Jefferson McKalb–recorded the statements, sitting on the last bench beneath the bower, his eyes sulky. The Indians listened. They muttered among themselves. They quieted, and Chief Peopeomoxmox of the Wallawalla rose, his nose as pugnacious-looking as Kamiakan’s, his nostrils flaring dismissively at Dominique. “I remember this one from when a Californian shot my son,” he said. “This one spoke like an owl coughing rabid mice. He said the white law would hunt and hang my son’s killer. He said this many times. But the white law hunted no one but Indians.”

Chief Stickus of the Cayuse rose, a silk ascot tied to his buckskin, his small eyes squinting darkly, piercingly. “I have known Dominique Purcell since before Reverend Whitman came, but now I cannot believe his words.”

The governor beckoned me. I rose and stood beneath the bower to speak, seeing Lalooh’s mother and aunts sitting in the nearest semicircle of squaws, heads alertly raised, hair-parts bare and glistening, braids tight as ropes, shiny as polished musket-barrels. Lalooh was not with them, not behind them, not with any group of squaws, and I had heard nothing of her since Jake and I had left her people.

I repeated Dominique’s translation exactly, “The Great Father will not steal his red children’s land. He will pay them more than it is worth. He will draw lines, so the whites and the Indians will know what they own. The Great Father will cede his children two reservations, so they can become rich in cattle and farms. The Great Father will give the Yakama, Klickitat and Palus land up the Yakama Valley. He will give the Cayuse, Umatilla and Wallawalla land up the Snake River and in Nez Perce country. His red children will get flour and corn easier to harvest than camas and bitterroot–wooden houses sturdier than lodges—sawmills, gristmills, blacksmith shops–unbreakable axes, shovels, blades and plows. His red women will get a chance to learn to spin and weave and make their own clothes. His red men will someday be doctors, lawyers and farmers just like whites.”

“Now we see the governor himself speaks roundabout, tending to evil,” said Peopeomoxmox. “We will take no gifts, not a grain of wheat. The Wallawalla want our own land. We Indians here are many bands, many chiefs. We will talk among ourselves and council again with whites at a better time.”

The governor raised a handbill: Gold on the Okanogan! At Kettle Falls! At Colville! “You have no time to waste,” he said. “Miners will come, and you must let them pass. The bad ones will take any squaw found off a reservation. They will steal your children if they find them off reservations.”

Dominique and I hid our chagrin behind our smiles, for no one had told us about a strike.

“We will give each chief his own house, gardens, five hundred dollars per year,” I translated. “Tell me, what does Kamiakan say? Does he have no heart to help his people?”

“Kamiakan has nothing to say,” said Kamiakan.

“Can this be true?” said the governor. “Kamiakan, great chief of the Yakama, does not speak? His people have no voice here today? Is he not afraid? Ashamed? No? Then speak out!”

I translated, and Kamiakan remained dead-faced. “What have I to speak of?” he said, and he slid his immense-dark gaze to columns of dust billowing suddenly down a low-sloping butte beyond the council grounds–more Cayuse arriving. Warriors painted fantastic colors fanned out, galloped down into Mill Creek, charged splashing up the bank. They raised spears and muskets, clanging shields, singing, circling Dragoons who stood stiffly at attention. The governor in his scarlet neck-scarf and balloon-sleeved blouse walked briskly past the soldiers. He stopped before Blue Hawk waiting high on a stallion, the Cayuse war chief wearing a coyote-head war cap, bear claws dangling, eagle plumes stained vermillion. The governor gestured at kettles of white beef, and Blue Hawk jerked his stallion around, and all the warriors followed, going to eat at Kamiakan’s camp, and Dominique counted, noting the number in his red-leather notebook, adding them to his previous count, making nearly two thousand.

And I wrote that evening in the governor’s tent, finishing his dispatch to Major Wells at Fort Dalles, “Three thousand warriors surround us as if to annihilate us, but Kamiakan and all the other chiefs see the wisdom of extinguishing their titles and accepting reservations. Five hundred more troops will keep the hot-blooded young ones cool with fear of our howitzers.”

The creek had stayed high a month, and a day or two after it had dropped inside its banks, Lalooh had busted up through silt-laden willow, raising a team whip, yelling, “Wah’k-puch!” Rattlesnake. She had snapped the whip behind Sidalia’s cabin, her arm jerked, the whip caught, and another lashed backward, untangling from hers, and I saw Sidalia jerk its handle. He was behind the cabin, and he turned and lashed the ground, and a snake leapt, spraying blood in a pop of dust. The rattler lifted its head. It coiled. It burred, and Sidalia drew his whip, and a crack snapped at his hand. His whip-handle flew from him, he grabbed his hand, sucked it, eyed Lalooh disbelieving, and she stepped evenly toward him, raising her whip again, and I could not think in Yakama, though I had been on my way to help Sidalia and Lalooh list words in his Yakama dictionary.

“Whoa!” I yelled in English, “Ko-pet’!” in Chinook. Stop.

Lalooh raised her whip higher, and Sidalia lifted his crucifix, thrust it toward her, planted his feet, his robe billowing in the wind as he stiffened. “Here I am, Lalooh! Strike me! Behold my medicine! My tah! Christ does not fear! I do not fear!”

“Chemookdatpas pelton!” said Lalooh. “Only Almcotty kills Wah’k-puch! Only the Indian doctor! No white! No devil robe!”

I ventured toward Lalooh, waving my hat at the snake, “It’s gone, Lalooh!”

“Gone?” Sidalia arched a glare toward me, keeping the crucifix aimed at Lalooh. “Would you die in the garden, Andrew? Would you have Jake die?”

“Wah’k-puch knows the bad medicine,” said Lalooh. “Wah’k-puch will send his men, and they will bite the bad father.”

“And then I will know the sweet sound of grace which speaks without a sound,” said Sidalia.

His dimples rose, his eyes shone brightly, and Lalooh’s whip cracked. The crucifix flew, its chain burst. Sidalia’s hair fluffed, barely missed. “Lalooh, Sparkling Water,” he said, translating her name. “The good father loves Lalooh.” He signed to sprinkle holy water on her head, mine, Jake’s, and Lalooh looked at me, lowering her whip, not understanding, and I thought of locust-eyed preachers sweating, speaking heatedly in Illinois, emigrant camps, Brownsville, other towns in Willamette Valley.

Lalooh looked at Sidalia, “Kamiakan told me, yes, I can put Yakama words in your book. But you go against Kamiakan. He told you black robes do not kill Wah’k-puch.”

She walked down into the creek again, mounting her pony, a huckleberry roan waiting on the opposite bank. But she returned the next Sunday–perhaps ordered by Kamiakan–or curious about Young Andrew?